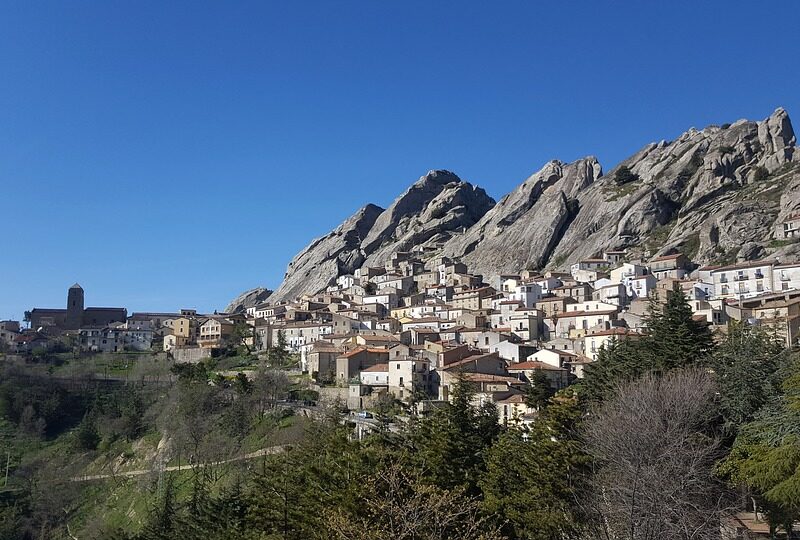

The Borgo of Fornelli

Fornelli is set like undulating jewels on the crest of a rocky ridge overlooking the Valley of Volturno. The borgo is an exquisite masterpiece framed by stretches of forests and olive groves, a magical stone kingdom of dream-like perfection.

Fornelli is protected by its ancient city walls, its seven towers watching over the red roofs and the ancient traditions of its inhabitants, the exposed stone of its buildings and the ancient stone lanes creating a Medieval atmosphere of irresistible fascination.

The borgo is a delicate weaving of curving stone stairways and cobblestone streets that intersect with arches opening onto beautiful little public squares.

In Fornelli, love floats in the air, in the rich and fruity scent of its olive oil and in the flavorful abundance of its traditional dishes, welcoming everyone to the table and cheering the spirit.

This borgo is tiny but stupendous, when the sun is shining in the clean blue mountain sky, when the snow is resting softly on the sloping roofs, and especially at sunset, when the delicate shades of red, violet and brilliant orange tinge the mountain peaks, and Fornelli is illuminated with a magical light that takes your breath away and fills your heart with wonder.

History

Fornelli stands on predominantly clay-rich soil, which suggests that since antiquity there has been a central kiln for firing bricks and ceramics here, in fact the name ‘Fornelli’ means stove or furnace in Italian.

The first written document attesting the existence of Fornelli dates back to 981 AD, elaborating a ruling on a dispute between the monks of the Abbey of San Vincenzo al Volturna and some colonists. Fornelli certainly existed before this document, but we need to go further back in time to understand the dynamics involved. The borgo probably began as a small village founded by the monks of the Abbey of San Vincenzo al Volturno for the purpose of cultivating the land. Unfortunately, the borgo was subjected to violent raids and looting from ruthless bands of Saracen Turks, and the village began to progressively depopulate, as the inhabitants either escaped to safer havens or were systematically killed off by the invaders. To remediate this demographic decline and reinvigorate farming activities, the resourceful monks began encouraging the arrival of immigrants from Valva (Sulmona) and other villages in central Italy.

In the twelfth century, the monks ceded the territory to the Normans, who built a fortress with a square structure and strengthened the previously existing city walls.

In 1438, Francesco Pandone managed to take control of the feif, which remained the property of his family until the sixteenth century, when Federico Pandone was forced to hand it over to the state to cover outstanding debts.

From this point on, Fornelli passed into the hands of various feudal dynasties, among them the Di Capua family, the Caracciolo family, and finally in 1667, the Carmignano family who restructured the Palazzo Baronale.

In 1744, the Carmignano family had a very special guest, King Charles III of the Bourbons. Still today, the rooms that were allocated to the sovereign are known as ‘The Alcove of Charles III’.

In 1814, the citizens decided to purchase a clock to install in the borgo’s bell tower, but unfortunately, the village is located in a highly seismic area, and the last earthquake of 1984 irreparably damaged the clock. In 2000, thanks to the donations of Fornelli citizens now living in the United States, it was possible to buy a new clock that rings the hours and quarters of an hour just like the original.

In 1832, the Carmignano family sold the fief the Laurelli dynasty, who once again restored the Baronial Palace, but were not particularly popular with the townspeople.

In 1943, a tragic event shook Fornelli: after the Armistice of the Second World War, the occupying German troops began to loot and pillage the little borgo in Molise, and one of the townspeople refused to be robbed, killing a German soldier in the process. As the man was a fervent anti-fascist, and already known for his ‘subversive’ activities the Germans made an example of him, condemning him and his companions to public hanging. Luckily, some of the group managed to escape by stealing an enemy truck. During their orgy of looting and pillaging the German soldiers even set the castle on fire, destroying the roof and countless ancient documents, pieces of the mosaic of Fornelli’s history that can never be replaced. A plaque at the site of this tragedy commemorates the event, which was officially recognized by the President of the Repubblica, Giovanni Leone in 1971, awarding Fornelli with Medal of Honor for ‘Military Valor in the War of Liberation’.

Today, Fornelli is a cheerful and serene borgo, and since 1997 it has been a member of the agricultural association, “Città dell’Olio” (The Cities of Olive Oil), which has generated increased demand for the numerous local olive oil producers, stimulating the city’s economy.

The City Walls and the Seven Towers

Fornelli is known as the ‘The Town of Seven Towers’. The ancient borgo is enclosed by city walls that are some of the best preserved in Molise.

The first defensive architecture of the borgo dates back to the period before the year 1000 AD, when Fornelli was an agricultural village serving the Benedictine monks of the Abbey of San Vincenzo al Volturno. With the advent of Norman rule, the perimeters of the city walls were enlarged and seven towers were constructed, as well as a central tower, or ‘keep’, which could be entered by crossing a drawbridge over a moat. Two of the seven towers are an integral part of the castle, while four of the towers have been incorporated into urban homes. The seventh tower is the principal tower, which opens onto the historical center. The towers were connected to each other by an external walkway, which today is known as the Via del Belvedere, for its superb views overlooking the lush expanse of forests and olive groves surrounding the borgo

Chiesa di San Michele Arcangelo, The Church of St. Michael the Archangel

The Church of San Michele Arcangelo faces a small public square. The building is dominated by an imposing bell tower that was added in 1738. The church has undergone numerous remodeling intervention over the centuries, which has left little of the original building. Small yet fascinating elements still reflect the fourteenth century portal, but the vaulted ceilings have been removed. The interior has three naves, with two arches dividing the rooms. The altars along side walls of the church are surmounted by paintings of the Madonna and various saints, among them San Nicola, or St. Nicholas.

Palazzo Baronale, The Baronial Palace

The ancient center of Fornelli was built at the top of a hill, and the Palazzo Baronale and the main Church of San Michele Arcangelo were also constructed in strategic, defensive positions.

Two historical phases can be identified for the Palazzo Baronale: the first is its original construction in the Lombard period, the traces of which have been lost, while in the second phase its appearance was altered to become more refined and pleasing to the eye, thanks to the influence of Duke Carmignano and his heirs, who sought to create an elegant residence appropriate to their noble rank.

Over time, the palace was extended toward the city walls, until it incorporated the Angevin towers which were transformed into pigeon roosts or “colombaie. This explains why the front of the building is more recent, hiding and protecting the ancient structure within.

In 1832, the Carmignano family sold the fief of Fornelli to Ippolito Laurelli, who implemented the most recent remodeling interventions to the Palazzo, which involved a super-elevation of the structure toward the main church, and the closure of the Palace courtyard, favoring the entrance to the Chapel Addolorata.

Since 1993, the Palazzo Baronale di Fornelli has been subject to restrictions and vetoes regarding further modifications to the structure, under the protection and surveillance of the Archeological Superintendence for the Artistic and Historical Heritage of Molise.

La fontana dell’Estate e la chiesa di San Pietro Martire, The Summer Fountain and the Church of St. Peter the Martyr

One of the little squares in the village of Fornelli holds two little gems that are not to be missed:

The Fontana dell’Estate and the little church of San Pietro Martire.

Originally called ‘La fontaine d’été’, it is an exact replica of the fountain created by the French sculptor Mathurin Moreau presented at the Paris World Fair in 1867. The fountain is made of cast iron and is commonly known as “The Reaper”.

The church of San Pietro Martire has Renaissance door and a façade with Baroque influences in its décor. The truly unique aspect of this church is the statue of St. Peter, which is perhaps the only existing statue of him depicted with a knife plunged directly into his head.

‘Sciur c Coccia’

Nothing brings people together like good food, as the inhabitants of Fornelli well know. There is no disagreement that does melt away when accompanied by a delicious dish of Casc’ e ova, kid’s livers with eggs and cheese, and no one can resist smiling when served the tasty cioffe at Carnival time, to name just a few examples.

The traditional dishes of Fornelli have the spectacular advantage of being accompanied by one of the best quality, most flavorful olive oils in Italy, produced in the expanses of olive groves that surround the area.

From the bounty of traditional recipes we have chosen the sciur c coccia , a truly mouthwatering delight.

Ingredients for four people:

- 8- 10 zucchini flowers;

- 200 gr of pale beer;

- 125 gr. of 00 flour;

- 2 eggs;

- Two tablespoons of olive oil;

- Salt as needed .

Preparation:

In a mixing bowl, sift the flour into a mound. Next, pour two tablespoons of beer, two egg yolks, and a pinch of salt into the center of the mound and start mixing, adding the remaining flour and beer as you mix. Whip the egg whites into peaks and then add to the mix.

The result is a homogeneous, well-mixed batter which must be left to rest for two hours.

Meanwhile, take the zucchini flowers and delicately remove the pistil. After two hours, start heating the oil in a frying pan, and when the oil is bubbling, quickly dip the zucchini flowers into the batter and then put them immediately into the oil. Fry the zucchini flowers until they are golden brown and remove from the pan, first placing them on paper towels to drain the excess oil, and then arrange them on your serving dish.

The sciur c coccia is a traditional dish in many other villages, with many different names. One scrumptious variation is to stuff the zucchini flowers before frying with cubes of provolone cheese, sardines, and capers. “Buonissimi!”

_________________________________

Do you known other typical recipes related to this borgo? Contact us!

Italiano

Italiano

Deutsch

Deutsch